What is Risk? How can risk of securities be calculated? Explain your answer with example.

Q1. What is Risk? How can

risk of securities be calculated? Explain your answer with example.

Risk

in holding securities is generally associated with the possibility that

realized returns will be less than the returns that were expected. The source

of such disap-pointment is the failure of dividends (interest) and/or the

security’s price to materialize as expected. Forces that contribute to

variations in return-price or dividend (interest)-constitute elements of risk.

Some influences are external to the firm, cannot be controlled, and affect

large numbers of securities. Other influences are internal to the firm and are

controllable to a large degree. In investments, those forces that are

uncontrollable, external, and broad in their effect are called sources of

systematic risk. Conversely, controllable internal factors somewhat peculiar to

industries and/or firms are referred to as sources of unsystematic risk. The

words risk and uncertainty are used interchangeably. Technically, their

meanings are different. Risk suggests that a decision maker knows the possible

consequences of a decision and their relative likelihoods at the time he makes

that decision. Uncertainty, on the other hand, involves a situation about which

the likelihood of the possible outcomes is not known. Systematic risk refers to

that portion of total variability in return caused by factors affecting the

prices of all securities. Economic, political, and sociological changes are

sources of systematic risk. Their effect is to cause prices of nearly all

individual common stock and/or all individual bonds to move together in the

same manner. For example, if the economy is moving toward a recession and

corporate profits shift downward, stock prices play decline across a broad

front. On the average, 50 percent of the variation in a stock’s price can be

explained by variation in the market index. In other words, about one-half the

total risk in an average common stock is systematic risk. Unsystematic risk is

the portion of total risk that is unique to a firm or indus-try. Factors such

as management capability, consumer preferences, and labor strikes cause

systematic variability of returns in a firm. Unsystematic factors are largely

independent of factors affecting securities markets in general. Because these

factors affect one firm, they must be examined for each firm.

Systematic Risk

Market Risk

Finding stock prices falling from time to time while a company’s earnings are

ris-ing, and vice versa, is not uncommon. The price of stock may fluctuate

widely within a short span of time even though earnings remain unchanged. The

causes of this phenomenon are varied, but it is mainly due to change in

investors’ attitudes toward equities in general, or toward certain types or

groups of securities in partic-ular. Variability in return on most common

stocks that is due to basic sweeping changes in investor expectations is

referred to as market risk. Market risk is caused by investor reaction to

tangible as well as intangible events. Expectations of lower corporate profits

in general may cause the larger body of common stocks to fall in price.

Investors are expressing their judgment that too much is being paid for

earnings in the light of anticipated events. The basis for the reaction is a

set of real, tangible events-political, social, or economic. Intangible events

are related to market psychology. Market risk is usually touched off by a

reaction to real events, but the emotional instability of investors acting

collectively leads to a snowballing overreaction. The initial decline in the

market can cause the fear of loss to grip investors, and a kind of herd

instinct builds as all investors make for the exit. These reactions to

reactions frequently culminate in excessive selling, pushing prices down far

out of line with fundamen-tal value. With a trigger mechanism such as the

assassination of a politician, the threat of war, or an oil shortage, virtually

all stocks are adversely affected. Like-wise, stocks in a particular industry

group can be hard hit when the industry goes “out of fashion

Interest Rate Risk

Interest-rate risk refers to the uncertainty of future market values and of the

size of future income, caused by fluctuations in the general level of interest

rates. The root cause of interest-rate risk lies in the fact that, as the rate

of interest paid on government securities rises or falls, the rates of return

de-manded on alternative investment vehicles, such as stocks and bonds issued

in the private sector, rise or fall. In other words, as the cost of money changes

for nearly risk-free securities, the cost of money to more risk-prone issuers

(private sector) will also change. The direct ef-fect of increases in the level

of interest rates is to cause security prices to fall across a wide span of

investment vehicles. Similarly, falling interest rates precipitate price

markups on outstanding securities. In addition to the direct, systematic effect

on bonds, there are indirect effects on common stocks. First, lower or higher

interest rates make the purchase of stocks on margin more or less attractive.

Higher interest rates, for example, may lead to lower stock prices because of a

diminished demand for equi-ties by speculators who use margin. Ebullient stock

markets are at times propelled to some excesses by margin buying when interest

rates are relatively low. Second, many firm such as public utilities finance

their operations quite heavily with borrowed funds. Others, such as financial

institutions, are principally in the business of lending money. As interest rates

advance, firms with heavy doses of borrowed capital find that more of their

income goes toward paying interest on borrowed money. This may lead to lower

earnings, dividends, and share prices. Advancing interest rates can bring

higher earnings to lending institutions whose principal revenue source is

interest received on loans. For these firms, higher earn-ings could lead to

increased dividends and stock prices.

Purchasing Power

Risk Market risk and interest-rate risk can be defined in terms of uncertainties

as to the amount of current rupees to be received by an investor.

Purchasing-power risk is the uncertainty of the purchasing power of the amounts

to be received. In more everyday terms, purchasing-power risk refers to the

impact of inflation or deflation on an investment. If we think of investment as

the postponement of consumption, we can see that when a person purchases a

stock, he has foregone the opportunity to buy some good or service for as long

as he own the stock. If, during the holding period, prices on desired goods and

services rise, the investor actually loses purchasing power. Rising prices on

goods and services are normally associated with what is re-ferred to as

inflation. Falling prices on goods and services are termed deflation. Both inflation

and deflation are covered in the all-encompassing term purchasing -power risk.

Generally, purchasing-power risk has come to be identified with infla-tion

(rising prices); the incidence of declining prices in most countries has been

slight. Rational investors should include in their estimate of expected return

an al-lowance for purchasing-power risk, in the form of an expected annual

percentage change in prices. If a cost-ofliving index begins the year at 100

and ends at 103, we say that the rate of increase (inflation) is 3 percent

[(103-100)/100]. If from the sec-ond to the third year, the index changes from

103 to 109; the rate is about 5.8 percent [(109-103)/103]. Just as changes in

interest rates have a systematic influence on the prices of all securities,

both bonds and stocks, so too do anticipated purchasing-power changes manifest

themselves. If annual changes in the consumer price index or other measure of

purchasing power have been averaging steadily around 3.5 percent, and prices

will apparently spurt ahead by 4.5 percent over the next year, re-quired rates

of return will adjust upward. This process will affect government and corporate

bonds as well as common stocks. Market, purchasing power, and interest-rate

risk are the principle sources of systematic risk in securities; but we should

also consider another important cate-gory of security risks-unsystematic risks.

Unsystematic Risk

Unsystematic

risk is that portion of total risk that is unique or peculiar to a firm or an

industry, above and beyond those affecting securities markets in general.

Factors such as management capability, consumer preferences, and labor strikes

can cause unsystematic variability of returns for a company’s stock. Because

these factors affect one industry and/or one firm, they must be examined

separately for each company. The uncertainty surrounding the ability of the

issuer to make payments on se-curities stems from two sources: (1) the

operating environment of the business, and (2) the financing of the firm. These

risks are referred to as business risk and finan-cial risk, respectively. They

are strictly a function of the operating conditions of the firm and the way in

which it chooses to finance its operations.

Business Risk

- Business risk is a function of the operating conditions faced by a firm and

the vari-ability these conditions inject into operating income and expected

dividends. In other words, if operating earnings are expected to increase 10

percent per year over the foreseeable future, business risk would be higher if

operating earnings could grow as much as 14 percent or as little as 6 percent

than if the range were from a high of 11 percent to a low of 9 percent. The

degree of variation from the expected trend would measure business risk.

Business risk can be divided into two broad categories: external and internal.

Internal business risk is largely associated with the efficiency with which a

firm con-ducts its operations within the broader operating environment imposed

upon it. Each firm has its own set of internal risks, and the degree to which

it is successful in coping with them is reflected in operating efficiency. To a

large extent, external business risk is the result of operating conditions

imposes upon the firm by circumstances beyond its control. Each firm also faces

its own set of external risks, depending upon the specific operating

environmental factors with which it must deal. The external factors, from cost

of money to defense-budget cuts to higher tariffs- to a downswing in the

business cycle, are far too numerous to list in detail, but the most pervasive

external risk factor is proba-bly the business cycle. The sales of some

industries (steel, autos) tend to move in tandem with the business cycle, while

the sales of others move counter cyclically (housing). Demographic

considerations can also influence revenues through changes in the birthrate or

the geographical distribution of the population by age, group, race, and so on.

Political policies are a part of external business risk; gov-ernment policies

with regard to monetary and fiscal matters can affect revenues through the

effect on the cost and availability of funds. If money is more expen-sive,

consumers who buy on credit may postpone purchases, and municipal gov-ernments

may not sell bonds to finance a water-treatment plant. The impact upon retail

stores, television manufacturers, and producers of water-purification sys-tems

is clear.

Financial Risk -

Financial risk is associated with the way in which a company finances its

activities. We usually gauge financial risk by looking at the capital structure

of a firm. The presence of borrowed money or debt in the capital structure

creates fixed pay-ments in the form of interest that must be sustained by the

firm. The presence of these interest commitments - fixed-interest payments due

to debt or fixed-divi-dend payments on preferred stock-causes the amount of

residual earnings avail-able for common-stock dividends to be more variable

than if no interest payments were required. Financial risk is avoidable risk to

the extent that managements have the freedom to decide to borrow or not to

borrow funds. A firm with no debt fi-nancing has no financial risk. By engaging

in debt financing, the firm changes the characteristics of the earnings stream

available to the common-stock holders. Specifically, the reliance on debt

financing, called financial leverage, has at least three important effects on

common-stock holders.” Debt financing (1) increases the variability of their

re-turns, (2) affects their expectations concerning

Assigning

Risk Allowances (Premiums) One way of quantifying risk and building a required

rate of return (r), would be to express the required rate as comprising a risk

less rate plus compensation for individual risk factors previously enunciated,

or as: r = i + p + b + f + m + o Where: i = real interest rate (risk less rate)

p = purchasing-power-risk allowance b = business-risk allowance f =

financial-risk allowance m = market-risk allowance o = allowance for “other”

riskThe first step would be to determine a suitable risk less rate of interest.

Unfor-tunately, no investment is risk-free, The return on Treasury bills or an

insured savings account, whichever is relevant to an individual investor, can

be used as an approximate risk less rate. Savings accounts possess

purchasing-power risk and are subject to interest-rate risk of income but not

principal government bills are subject to interest-rate risk of principal. The

risk less rate might by 8 percentTo quantify the separate effects of each type

of systematic and unsystematic risk is difficult because of overlapping effects

and the sheer complexity involved.

Stating Predictions “Scientifically”

Security

analysts cannot be expected to predict with certainty whether a stock’s price

will increase or decrease or by how much. The amount of dividend income may be

subject to more or less uncertainty than price in the estimating process. The

reasons are simple enough. Analysts cannot understand political and

socioeco-nomic forces completely enough to permit predictions that are beyond

doubt or error. This existence of uncertainty does not mean that security

analysis is value-less. It does mean that analysts must strive to provide not

only careful and rea-sonable estimates of return but also some measure of the

degree of uncertainty associated with these estimates of return. Most

important, the analyst must be prepared to quantify the risk that a given stock

will fail to realize its expected return. The quantification of risk is

necessary to ensure uniform interpretation and comparison. Verbal definitions

simply do not lend themselves to analysis. A deci-sion on whether to buy stock

A or stock B, both of which are expected to return 10 percent, is not made easy

by the mere statement that only a “slight” or “minimal” likelihood exists that

the return on either will be less than 10 percent. This sort of vagueness

should be avoided. Although whatever quantitative measure of risk is used will

be at most only a proxy for true risk, such a measure provides analysts with a

description that facilitates uniform communication, analysis, and ranking.

Pressed on what he meant when he said that stock A would have a return of 10

percent over some holding period, an analyst might suggest that 10 percent is,

in a sense, a “middling” estimate or a “best guess.” In other words, the return

could be above, below, or equal to 10 percent. He might express the degree of

confidence he has in his estimate by saying that the return is “very likely” to

be between 9 and 11 percent, or perhaps between 6 and 14 percent. A more

precise measurement of uncertainty about these predictions would be to gauge

the extent to which actual return is likely to differ from predicted

re-turn-that is, the dispersion around the expected return. Suppose that stock

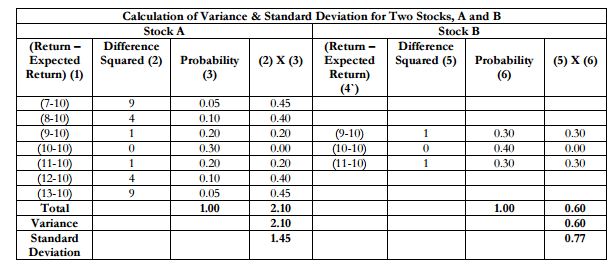

A, in the opinion of the analyst, could provide returns as follows:

This

is similar to weather forecasting. We have all heard the phrase a 2-in-10

chance of rain. This likelihood of outcome can be stated in fractional or

decimal terms. Such a figure is referred to as a probability. Thus, a 2-in-10

chance is equal to 2/10, or 0.10. A likelihood of four chances in twenty is

4/20, or 0.20. When individ-ual events in a group of events are assigned

probabilities, we have a probability dis-tribution. The total of the

probabilities assigned to individual events in a group of events must always

equal 1.00 (or 10/10, 20/20, and so on). A sum less than 1.00 in-dicates that

events have been left out. A sum in excess of 1.00 implies incorrect as-signment

of weights or the inclusion of events that could not occur. Let us recast our

“likelihoods” into “probabilities.”

Based

upon his analysis of economic, industry, and company factors, the analyst

as-signs probabilities subjectively. The number of different holding-period

returns to be considered is a matter of his choice. In this case, the return of

7 percent could mean “between 6.5 and 7.5 percent.” Alternatively, the analyst

could have speci-fied 6.5 to 7 percent and 7 to 7.5 percent as two outcomes, rather

than just 7 per-cent. This fine-tuning provides greater detail in prediction.

Security analysts use the probability distribution of return to specify

expected return as well as risk. The expected return is the weighted average of

the returns. That is, if we multiply each return by its associated probability

and add the results together, we get a weighted-average return or what we call

the expected average return

The

expected average return is 10 percent. The expected return lies at the center

of the distribution. Most of the possible outcomes lie either above or below

it. The “spread” of possible returns about the expected return can be used to

give us a proxy of risk. Two stocks can have identical expected returns but

quite different spreads, or dispersions, and thus different risks. Consider

stock B:

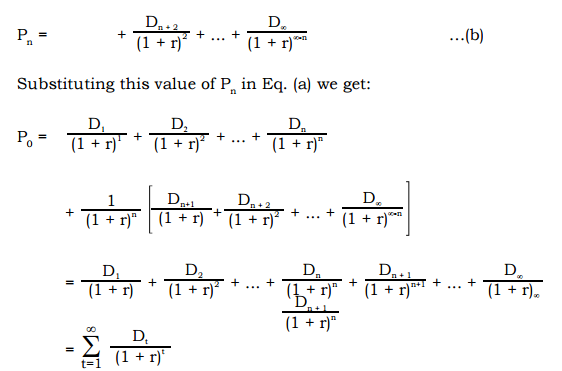

In

general, the expected return, variance, and standard deviation of outcomes can

be shown as: R = S i n =1 Pi Oi s 2 = S i n =1 Pi (Oi - R)2 s = (s) 1/2 Where,

R = expected return ó 2 = variance of expected return ó = standard deviation of

expected return P = probability O = outcome n = total number of different

outcomes The variability of return around the expected average is thus a

quantitative descrip-tion of risk. Moreover, this measure of risk is simply a

proxy or surrogate for risk because other measures could be used. The total

variance is the rate of return on a stock around the expected average that

includes both systematic and unsystematic risk

Comments

Post a Comment