Risk Return Trade off

Risk Return Trade

off

The world of investing can be a cold, chaotic, and confusing place. In this tutorial, we'll go through some of the theories that investors have developed in an effort to explain the behaviour of the market. We will discuss concepts, like risk return trade-off, rupee cost averaging and diversification, that are especially useful for individual investors. Deciding what amount of risk you can take while remaining comfortable with your investments is very important.

The world of investing can be a cold, chaotic, and confusing place. In this tutorial, we'll go through some of the theories that investors have developed in an effort to explain the behaviour of the market. We will discuss concepts, like risk return trade-off, rupee cost averaging and diversification, that are especially useful for individual investors. Deciding what amount of risk you can take while remaining comfortable with your investments is very important.

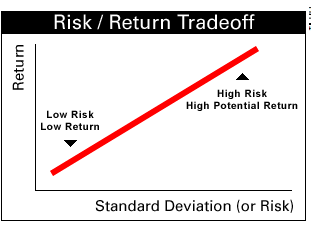

In

the investing world, the dictionary definition of risk is the chance that an

investment's actual return will be different than expected. Technically, this

is measured in statistics by standard deviation. Practically, risk means you

have the possibility of losing some or even all of your original investment.

Low

risks are associated with low potential returns. High risks are associated with

high potential returns. The risk return trade-off is an effort to achieve a

balance between the desire for the lowest possible risk and the highest possible

return. The risk return trade-off theory is aptly demonstrated graphically in

the chart below. A higher standard deviation means a higher risk and therefore

a higher possible return.

A

common misconception is that higher risk equals greater return. The risk return

trade-off tells us that the higher risk gives us the possibility of higher

returns. There are no guarantees. Just as risk means higher potential returns,

it also means higher potential losses.

On

the lower end of the risk scale is a measure called the risk-free rate of

return. It is represented by the return on 10 year Government of India

The

common question arises: who wants 6 per cent when index funds average 13 per

cent per year over the long run (last five years)? The answer to this is that

even the entire market (represented by the index fund) carries risk. The return

on index funds is not 13 per cent every year, but rather -5 per cent one year,

25 per cent the next year, and so on. An investor still faces substantially

greater risk and volatility to get an overall return that is higher than a

predictable government security. We call this additional return, the risk

premium, which in this case is 7 per cent (13 per cent - 6 per cent).

How

do you know what risk level is most appropriate for you? This isn't an easy

question to answer. Risk tolerance differs from person to person. It depends on

goals, income, personal situation, etc. Hence, an individual investor needs to

arrive at his own individual risk return trade-off based on his investment

objectives, his life-stage and his risk appetite.

Comments

Post a Comment